“Time races onwards ceaselessly.”—It seeks the unchanging.

Remain true, and you’ll cast eternal fetters over it.

—The Immutable, Epigram by Friedrich Schiller

Resignation

By Friedrich Schiller

I, too, was born in the fields of Arcadia,

While still in the cradle

Nature whispered her promises of joy.

I, too, was raised in the fields of Arcadia,

But the spring flowered only tears.

Life’s May bloomed once, and then never again,

And now it withers.

The silent God—weep fellow mortals—

The silent God has extinguished the flame.

The vision has fled.

I stand before this bridge of no return,

O dizzying Eternity!

Here is the contract for my happiness;

I hand it back to you perfectly sealed.

I forfeit earth’s joys.

Before your sacred throne I plead and wail,

My secret judge!

Your stars had once foretold a happy tale;

The scales of justice balanced at your throne.

Avenger was your name.

Here, men said, punishment awaits the evil,

And joys are heaped upon the good.

The labyrinth of men’s hearts is revealed,

The mysteries of Providence resolved,

And all is reckoned and accounted for.

Here, exiles return to their lasting home;

Here ends the trail of thorns the sufferer treads.

A divine child, whose name was Truth,

Whom many fled, and fewer understood,

Kept me from straying from the narrow path.

“I’ll pay you in the promised afterlife,

Now relinquish your youth!

This offering is all that’s asked of you.”

I made the bargain and embraced my fate,

Surrendering youth’s joys.

“Give me the woman dearest to your heart,

Give me your Laura!

You’ll be paid for your pain beyond the grave.”

I tore the woman from my bleeding heart,

And crying out, gave her to you.”

“This bond is redeemable by the dead”!

Ridiculed the world.

“This liar, who makes use of the despot’s tricks,

Offered you shadows in exchange for Truth!

You’ll be dead by the time redemption’s due.”

Mocked the snake-tongued hoards of derision:

“A delusion, consecrated by myth

Now frightens you? Who are your gods,

Who’ve devised such trickery, contrived by some worldly savior,

And offered to poor, witless men?

“What kind of future covers us in graves?

So-called Eternity is but in vain,

Worshipped only because it shrouds itself in veils—

Grave shadows hiding our own deepest fears

Within the mirror of our conscious guilt.”

“Deceiving images of living forms,

Preserved as the mummies of Time

Whose empty carcasses of embalmed hope

Are buried in the graveyards of this world.

You call this immortality?

“For cherished hopes, which life’s decay belies,

You rejected a certain good?

Yet for six thousand years death remains mute.

Has any corpse ever crawled from the grave

By calling the Avenger forth?”

I saw Time fading with its many hours,

And blooming nature

Remained pallid and withered like a corpse.

No dead man came and crawled out of his tomb,

Yet still I trusted in my sacred venture.

I’ve sacrificed the joys of this cold Earth,

And now I kneel before the judge’s throne.

I ignored all the crowds who balked and scorned,

Your goodness being cherished above all.

Avenger, I now claim my due.

“I love each of my children equally,”

Declared a hidden voice of genius.

“Two flowers,” he cried, “behold my children,

Two flowers bloom before the wise seeker,

And hope and pleasure are their names.”

“Whoever plucks one flower must forgo

Her sister’s blooms.

The hopeless search for joy, this teaching is

As old as time itself. Those who believe refrain!

The history of our own world’s the judge.”

“You held to hope and that is your reward,

Your happiness was in your faith.

You could have sought the counsel of the wise:

Eternity will not redeem the hours

And minutes man lets slip away.”

Translation © David B. Gosselin

Reflections and Analysis

In this dramatic lyrical poem composed by Friedrich Schiller during his middle period (1782-1788), the main character is confronted with the limitations of his own notions of Truth, Eternity, Salvation and personal Immortality. After confronting several different voices, a “hidden genius” emerges and offers him a friendly reminder.

The renowned polymath, diplomat, naturalist, German education reformer and close ally of Schiller, Alexandre von Humboldt, had the following to say about the poem:

“Resignation carries Schiller’s most characteristic stamp in the direct coupling of simply expressed, profound, great truth with incomparable images, and in the wholly original language which encourages the boldest combinations and constructions. The principal thoughts developed in the whole can only be seen as a transient mood of an emotionally charged mind, but it is so masterfully depicted that the passion is quite taken up into contemplation, and the expression seems to be solely the fruit of reflection and experience.”

“Resignation” is one of the German poet’s most popular poems. However, its popularity extended beyond Germany. For instance, Russian scholar J.A. Harvie describes the poem’s influence on many of Russia’s literary giants:

“Schiller's poem Resignation, written in 1784, was popular in Russia and is frequently mentioned in the literature. In 1807 the minor poet V.S. Filomonov made a free translation, which was published in the Vestnik Evropy (European Messenger) four years later, under the title K Laure (To Laura). It was also translated in the 1820s by Mikhail Dmitriev. Among other writers it was admired by Herzen and Dostoevsky; there is undoubtedly an allusion to it in The Brothers Karamazov, when Ivan tells Alesha that he will return God his entrance ticket to life. In Turgenev's story Yakov Pasynkov the hero of the title effectively bases his life on the rejection of Schiller's conclusions, while considering Resignation to be a splendid piece of writing. Tolstoy regarded the poem as one of Schiller's finest achievements.”

Schiller’s popularity among the leading musical composers of Europe, including Beethoven, Schubert, Schumann and Brahms, goes without saying. Just like Goethe, many of Schiller’s poems were set to music by the greatest composers, with Beethoven’s setting of “Ode to Joy” in the Ninth Symphony being only the most famous case.

“Resignation” describes a soul who stands at the bridge of no return, preparing to face Eternity. He describes the many promises made to him in the name of a child “called Truth” and the lampooning he suffered at the hands of disbelievers. Finally, he argues for the merits of his sacrifices and eligibility for a well-earned afterlife.

The poem captures the tension between the experiential and ascetic dimensions of any spiritual journey. Does one withhold and repress certain emotions and impulses on the promise of an afterlife, which redeems one’s worldly disappointments, abandoned hopes, and forgotten dreams? Or does one seize the moment—carpe diem—and strive to leave some lasting impression on time, in however humble a way?

As far as resolutions to this existential paradox, the poem offers no definite answers—hence the “resignation.” What Schiller does is capture the dramatic tension faced by a conflicted and admittedly adolescent-minded believer struggling with these spiritual matters. Arrived at the chasm of Eternity, the protagonist argues he’s checked off all the correct boxes, kept his vows, performed his duty, and now demands his promised immortality. The poem is in some ways reminiscent of Schiller’s “The Pilgrim,” where an equally disenchanted believer is left reeling after years of searching for the promise land on Earth, only to discover “there is never here.”

Ultimately, Schiller was confronting the drab spirituality of his time, which took the form of a very rarefied Christianity in which matters of faith, God and spiritual development were usually reduced to checking off a few boxes to cross the golden gates. However, as Schiller observed in his time, while many did their Kantian duty, utility was still the ruling idol of the age for the practical Germans.

So, Schiller’s notion of a “Schöne Seele” (beautiful soul) in his subsequent period looked to the question of ennobling the emotions as a necessary means of unfolding the greatest potential of each human being, therefore resolving the seeming contradictions between duty and inclination/freedom and necessity. Of course, this philosophical project seemed like a highly impractical proposition for most (as it still does today), but it laid out an aesthetic ideal whose practicality is arguably its most promising aspect, given Schiller’s notion of an aesthetic consciousness applies as much to evaluating a beautiful piece of art as it does developing a beautiful soul.

The relevance and practical implications of Schiller’s aesthetic education in respect to matters of law, justice and statecraft are also made clear in his essay “The Legislation of Lycurgus and Solon.”

He writes:

“Freedom of the will is the first condition for the moral beauty of actions, and this freedom is lost as soon as one tries to enforce moral virtue through legal punishments. The noblest prerogative of human nature is to determine oneself and to do good for the sake of good. No civil law may compulsorily command loyalty to one’s friend, generosity to one’s enemy, gratitude to one’s father and mother; for as soon as it does this, a free moral feeling is transformed into a work of fear, into a slavish impulse.”

With “Resignation” in mind, one might add that we also can’t compel the noblest forms of emotion, belief, faith or action merely through shame and the threat of punishment, either in this world or the next. Without beauty, the will can never be tamed, only suppressed (or oppressed). Emotions will always be caught between the pressing needs of matter and the eternal demands of the spirit, rather than resolved in a beautiful manner. So, Schiller believed men had to first beautify their instincts and will, which could only be done as an act of free choice. Those forms of art, culture and entertainment which had the moving power to strengthen the will were thus seen as the vital cultural force needed to shape the character of any mature civilization, lest character formation be reduced to nothing more than a sophisticated form of dog training and reflex conditioning.

However, Schiller’s poem concludes with a “spirit of Genius” who arguably introduces a more nuanced dimension to the conflicting and simpler forms of faith and happiness subscribed to by the poem’s protagonist. The voice emphasizes the importance of those brief mortal hours gifted to man. Man may choose to contribute something of lasting worth during his brief time on earth, and therefore cast eternal fetters over it. However, belief in the individual’s capacity for such lasting things arguably demands a deeper and more mature faith than the adolescent notion of an afterlife subscribed to by the narrator.

Given this poem was composed during Schiller’s middle period, it offers only a very small glimpse of his mature spiritual and intellectual development. But as Humboldt writes:

“The Philosophical Letters, published in Thalia, with which the poem Resignation, a product of the same year, has such a striking kinship in the bold sweep of its passionately philosophical reason, should have marked the beginning of a series of philosophical clarifications for Schiller. But the sequel was not forthcoming, and a new philosophical period began for Schiller in On Grace and Dignity, principally founded on his acquaintance with Kantian philosophy. Those two pieces could be regarded only with injustice, as expressing the writer’s actual opinions; they belong, however, among the best we have from him.”

Despite “Resignation” being composed before Schiller’s last and great third period, it is as Humboldt observes a passionate piece which invites the reader to meditate on the existential spiritual and philosophical paradoxes facing every mortal embarked on a spiritual quest.

In conclusion, the “voice of genius” perhaps serves as a modest basis for understanding the future development of Schiller’s ideas on aesthetic education, which had as their purpose the creation of whole and complete human beings capable of transcending the more conflicted notions of Truth, Time and Eternity faced by our hero. Regardless of his unwavering faith or pursuit of happiness, a hidden genius reminds him that Eternity never redeems “the hours and minutes man let’s slip away.”

Originally published by the Rising Tide Foundation

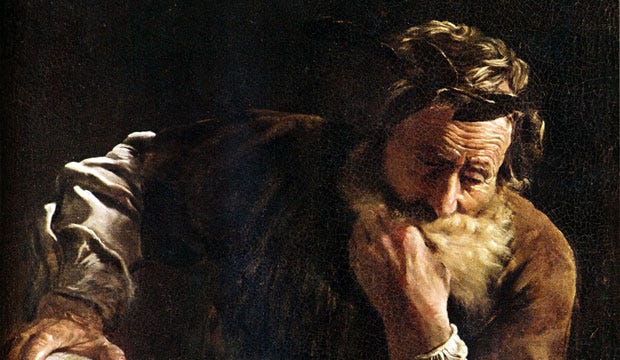

Reflections on Ideal Science and Art: Schiller’s “Archimedes and the Student”

We’ll be publishing regular new translations and analysis for our subscribers, all of which will be appearing in my new book of Schiller translations. We begin this new year with reflections on the ideal of science and art, as explored in Schiller’s “Archimedes and the Student.”

Why We Need the Tragic: Schiller, Cassandra and the Rebirth of Tragedy

“Trust me, the fountain of youth, it is no fable. It is running

From the Beautiful to the Sublime: On Schiller's "The Guides of Life"

Two kinds of genius may escort you throughout life.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Age of Muses to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.