An Archaic Revival or Classical Rebirth?

The Renaissance, Neoplatonism and the Magical un-Making of the Mystery Schools

With the replacement of the Pantheon and Rome’s vast array of mystery schools by Nicene Christianity, the soothsayers, astrologists, magicians and medicine men of old seemed to have been kicked to the curb for good. Further, with the Judeo-Christian notion of man as imago viva dei and capax dei revitalized and further elaborated during the Florentine Renaissance, the human intellect seemed to have triumphed over the most elaborate forms of archaic magic, Medieval sooth-saying and Delphic divination.

Or so we thought.

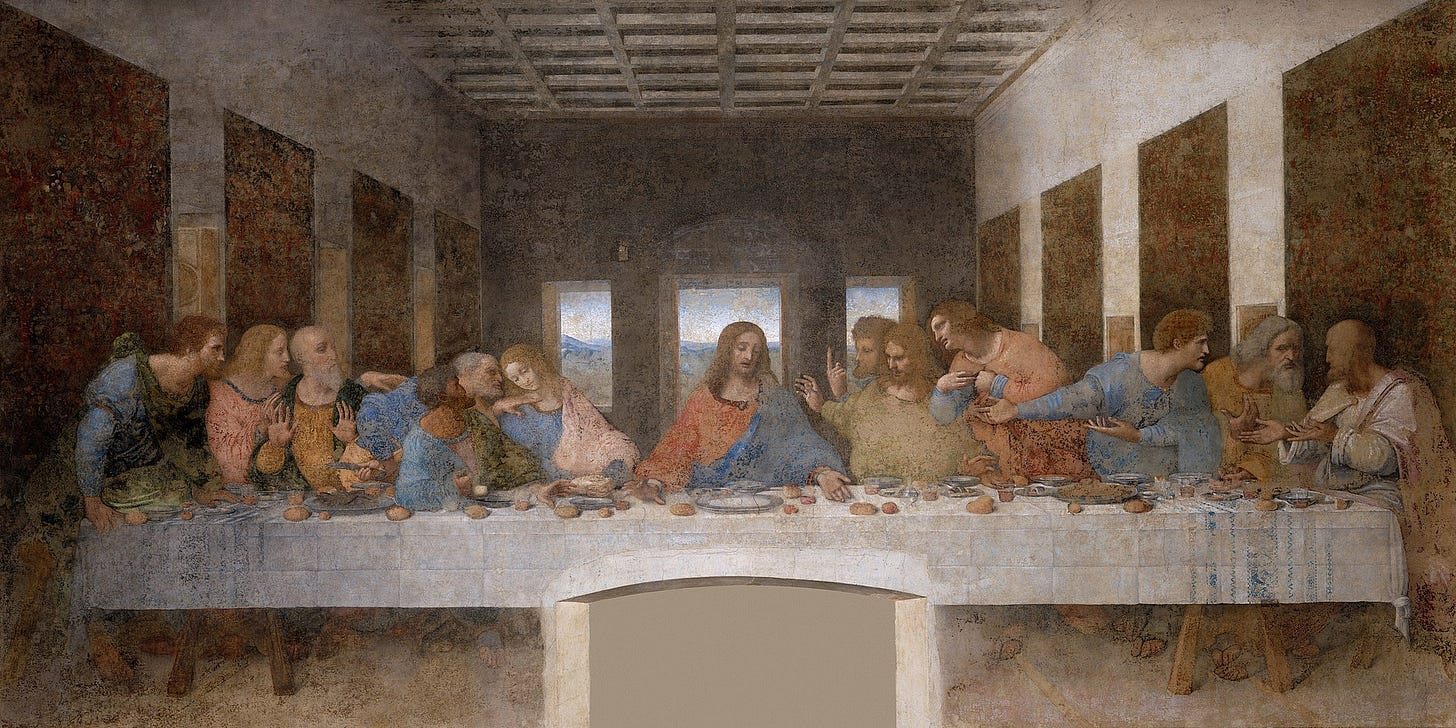

Initially, the revolution was exemplified by Renaissance geniuses like Leonardo Da Vinci who could conceive of the sacred Trinitarian relationship between man and God with revolutionary new artistic and scientific insights; the architect of a small Florentine city-state like Brunelleschi could build church domes greater than those constructed by history’s most celebrated empires; and a Tuscan poet like Dante could compose epic cycles whose philosophical vision and moral clarity would have been admired and admitted by the most stringent philosopher kings of Plato’s ideal Republic.

A coincidence between man and God, the microcosm and macrocosm, became a visceral reality, dwarfing the earlier forms of “magic.”

But while the occult mystery schools of ancient times, with their archaic myth-makers, weather-modifying Chaldean oracles, and soothe-saying spellcasters may have taken a back seat to the modern making of Western civilization, a closer examination of the true story of the Renaissance suggests the clever rain-makers and soothe-saying operators of old never really went away.

In reality, Western civilization’s current-day struggle for survival in the face of post-industrial despair, cultural degeneration and spiritual perversion can be traced back to the fact that there were not one but two Renaissances during the 15th century. As we’ll see, these two currents have been at war ever since, and are duking it out at this very moment, even as you read these lines.

What follows is a new chapter on the unfinished story of modern Western civilization and the ongoing efforts to unmake one of the greatest transformations in history.

The Haunting of Modern Man?

I think we must give it time to infiltrate into people from many centers, to revivify among intellectuals a feeling for symbol and myth, ever so gently to transform Christ back into the soothsaying god of the vine, which he was, and in this way absorb those ecstatic instinctual forces of Christianity for the one purpose of making the cult and the sacred myth what they once were, a drunken feast of joy where man regained the ethos and holiness of an animal.

—Carl Jung, Letters Vol. I, Page 18 (Letter to Sigmund Freud)

It’s become commonplace to describe man and the modern world as “haunted,” with most of humankind soullessly drifting without any roots or history, condemned to the blind worship of material prosperity and security, without any sense of its own divine nature. Perhaps no one articulated this view more effectively in the twentieth century than a famous occultist and black magician who doubled as a popular psychoanalyst, Carl Jung.

Jung gave a series of lectures on “Modern Man and his Search for a Soul” where he opined that:

“The modern man has lost all the metaphysical certainties of his medieval brother, and set up in their place the ideals of material security, general welfare and humaneness. But it takes more than an ordinary dose of optimism to make it appear that these ideals are still unshaken. Material security, even, has gone by the board, for the 'modern man begins to see that every step in material ‘progress’ adds just so much force to the threat of a more stupendous catastrophe. The very picture terrorizes the imagination. What are we to imagine when cities today perfect measures of defense against poison-gas attacks, and practice them in ‘dress rehearsals’”

Overlooking the many agencies, agendas and political operations used to actively unmake modern Western civilization and the fruits of its progress, Jung’s arguments have come to be associated with a wide range of “Traditionalist”, esoteric, and mysticism-prone ideological groupings who believe the modern world is essentially incompatible with man’s true “spiritual” nature. These currents have risen to great influence on both the ostensible “Right” and “Left” sides of the political spectrum.

Escaping Huxley’s Island: Psychedelics, Scientific Paganism and the Changing Images of Man

Originally published on UK Column

Under the duress of a collapsing Western monetary system and the modern malaise perpetuated by a nearly terminal cancerous financial growth that has attached itself to the West’s vital organs, a new Medieval romanticism has rooted itself in the imaginations of many diverse and seemingly opposed ideological currents. From eco-terrorists like Ted Kaczynski and self-styled traditionalist, orthodox, neo-monarchist and neo-paganist influencers to secular, environmentalist, New Age, and Accelerationist gurus—all have expressed their longing to see mankind cast off the artificial yoke of modern civilization—and therefore regain the “magic” of earlier times.

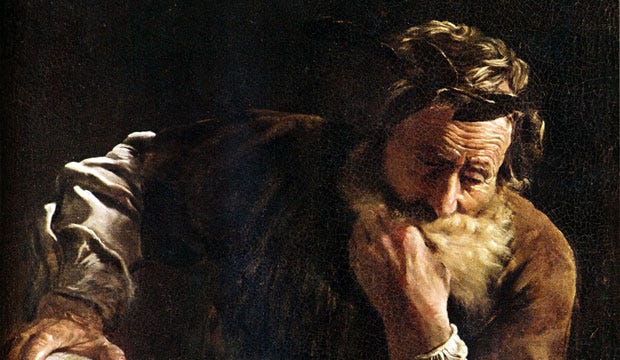

Consider why Carl Jung describes man’s leap from the Middle Ages into the modern world as something akin to a “Promethean sin”. As an avid enthusiast of ancient occultism, Neoplatonism, alchemy and Gnosticism, Jung remarked that the life of modern man was stripped of the “magic” and “mystery” which had animated the life of his medieval brothers and archaic ancestors.

Jung argues:

“In the face of such a picture we may well grow humble again. It is true that modern man is a culmination, but tomorrow he will be surpassed; he is indeed the end-product of an age-old development, but he is at the same time the worst conceivable disappointment of the hopes of humankind. The modern man is aware of this. He has seen how beneficial are science, technology and organization, but also how catastrophic they can be. He has likewise seen that well-meaning governments have so thoroughly paved the way for peace on the principle “in time of peace prepare for war,” that Europe has nearly gone to rack and ruin. And as for ideals, the Christian church, the brotherhood of man, international social democracy and the solidarity of economic interests have all failed to stand the baptism of fire—the test of reality.”

The suppression of the dark, numinous and intuitive forces prominent among archaic civilizations now haunted modern “rationalist” man, Jung believed. It was the source of war, strife and societal discontent. This “Promethean sin”—the emergence of the belief in a divine order governed by Reason, absent an irrational and arbitrary will—left man spiritually void. And while the modern mind could not admit magic into his system, Jung enjoyed using his psychoanalytic theories to diagnose the sabotaging, rankled modern mind, which struggled to comprehend the seemingly irrational outbursts of the psyche—despite his best rational efforts.

Jung believed only a reconnection with the occult, mystical and mysteries of old would give man the tools to reconnect with the deeper, divine and intuitive realm of the human psyche which was the supposed source of man’s sacred energy.

Jung writes:

“By means of the secular practice of the naïve projection which is, as we have seen, nothing else than a veiled or indirect real-transference (through the spiritual, through the logos), Christian training has produced a widespread weakening of the animal nature so that a great part of the strength of the impulses could be set free for the work of social preservation and fruitfulness. This abundance of libido, to make use of this singular expression, pursues with a budding renaissance (for example Petrarch) a course which outgoing antiquity had already sketched out as religious; viz., the way of the transference to nature. The transformation of this libidinous interest is in great part due to the Mithraic worship, which was a nature religion in the best sense of the word; while the primitive Christians exhibited throughout an antagonistic attitude to the beauties of this world.” (The Psychology of the Unconscious, Carl Jung)

The vital energies of man became fragmented and compartmentalized in the interest of a more “civilized” and “rational order.” This was also Freud’s conclusion, though he and Jung differed on solutions.

However, while Christianity and modern civilization were inextricably wed for Jung, given their emphasis on Reason, other “traditionalist” strands on the nominally Christian side of the ideological spectrum have echoed the same Medieval romanticism.

How could this be?

Writing in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and First World War, the Russian orthodox philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev offered a similar, though ostensibly Christian critique of the modern world and its origins in the Renaissance. Characterizing the height of Western scientific and technological progress of his time as a sign of the ultimate unmaking of the modern world and the beginnings of a “New Middle Ages”, Berdyaev foretold of a new “barbarization of Europe; after the refined corruption which marked the highest point of European culture the barbarian invasion has its turn… There may be a new chaos of peoples; the feudalization of Europe is a possibility. There is no such thing in the history of mankind as a continual progress upward in a straight line…”

In his collected works, The End of Our Times, which has inspired orthodox influencers like Alexander Dugin, Berdyaev writes, “The Renaissance began with the affirmation of man’s creative individuality; it has ended with its denial. Man without God is no longer man: that is the religious meaning of the internal dialectic of modern history, the history of the grander and of the dissipation of humanist illusions.” The end of the Renaissance and historical day would give way to what Berdyaev called the “universal night”, which entailed “the passage from modern rationalism to an irrationalism, or better to a super-rationalism, of the medieval type.”

A self-styled orthodox thinker much like Alexander Dugin, Berdyaev ironically foreshadowed today’s “Accelerationism” which encourages the accelerated decline of the modern world in order to make way for a new set of values.

Berdyaev, like Jung, along with many Traditionalists and neo-reactionaries somewhat gleefully welcomes the chaos, heralding it as a Providential restoration of divine order and the natural “darkness” that enshrouded and enchanted earlier Christian civilization. “And here we may well remind ourselves that the most terrible wars and revolutions, wrecking of civilizations, fall of empires, are not due solely to man’s ill-will but are also in a measure the work of divine providence,” writes Berdyaev.

Jung likewise argued that despite the undoubtably great achievements of modern civilization, from Classical Greece to Nicene Christianity, the Renaissance to the industrial revolution, modern man was as much a failure as a success:

“Now there is the danger that consciousness of the present may lead to an elation based upon illusion: the illusion, namely, that we are the culmination of the history of mankind, the fulfillment and the end-product of countless centuries. If we grant this, we should understand that is no more than the proud acknowledgement of our destitution: we are also the disappointment of the hopes and expectations of the ages. Think of nearly two thousand years of Christian ideals followed, instead of by the return of the Messiah and the heavenly millennium, by the World War among Christian nations and its barbed-wire and poison-gas. What a catastrophe in heaven and on earth!”

In the same way Berdyaev prognosticates the end of modern Western civilization using pseudo-spiritual and pseudo-philosophical arguments, Jung offers a pseudo-psychological assessment which ignores all the causal historical factors and agencies that have actively worked to subvert and unmake the modern world—many of them associated with occult schools of learning and banking syndicates tied to the most ancient oligarchical centers of power in the West.

Slaying Mithra: Self-help, Human Potential and the Luciferian Perversion of the West - Part I

For the radical and permanent transformation of personality only one effective method has been discovered — that of the mystics.

Each in their own way believed in a divine darkness that had as much a place and power as the light (if not more); and that the way out of the modern crisis lay in a return to darkness, away from the direction of Reason illuminated by the 15th Renaissance. Whether ostensibly Christian (i.e. Medieval Christianity) or Gnostic, Pagan, Chaldean, Neoplatonic or Mithraic, all are united in their conviction that Reason must be dethroned, and the legacy of the Renaissance undone.

Near the end of one of his philosophical memoirs, Jung writes:

“At last I had found confirmation that there were or had been people who saw evil and its universal power, and--more important—the mysterious role it played in delivering man from darkness and suffering. To that extent Goethe became, in my eyes, a prophet. But I could not forgive him for having dismissed Mephistopheles by a mere trick, by a bit of jiggery-pokery. * For me that was too theological, too frivolous and irresponsible, and I was deeply sorry that Goethe too had fallen for those cunning devices by which evil is rendered innocuous. In reading the drama I had discovered that Faust had been a philosopher of sorts, and although he turned away from philosophy, he had obviously learned from it a certain receptivity to the truth. Hitherto I had heard virtually nothing of philosophy, and now a new hope dawned. Perhaps, I thought, there were philosophers who had grappled with these questions and could shed light on them for me.” (Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections., p. 537)

The Science of the Jungle, or the Revenge of the Medicine Men

“Magic is the science of the jungle”

In one of his lectures, Jung recounts the memorable experience he had navigating the tropical forests of Africa:

“One must imagine the velvety blue of a tropical night, the overhanging black masses of gigantic trees standing in a virgin forest, the mysterious voices of the nocturnal spaces, a lonely fire with loaded rifles stacked beside it, mosquito-nets, boiled swamp-water to drink, and above all the conviction expressed by an old Afrikander who knew what he Was saying : ‘This isn't man's country-it's God's country.’ There man is not king ; it is rather nature - the animals, plants and microbes. Given the mood that goes with the place, one understands how it is that we found a dawning significance in things that anywhere else would provoke a smile. That is the world of unrestrained, capricious powers with which primitive man has to deal day by day. The extraordinary event is no joke to him. He draws his own conclusions. ‘It is not a good place’-‘The day is unfavourable’-and who knows what dangers he avoids by following such warnings?” (Archaic Man, p. 139-140)

Jung contrasted “the magic of the jungle” with the supposedly artificial world modern man had created for himself, one that he naively believed could insulate him from those arbitrary forces which shaped the faith and fate of all earlier primitive, archaic and ancient societies, that is, those periods during which the sorcerers, medicine men, rain-makers and oracles still ruled.

“A recent investigator has ventured the statement: ‘Magic is the science of the jungle.’ Astrology and other methods of divination may undoubtedly be called the science of antiquity. What happens regularly is easily observed because we are prepared for it. Knowledge and skill are only needed in situations where the course of events is arbitrarily disrupted in a way hard to fathom. Generally it is one of the cleverest and shrewdest men of the tribe who is entrusted with the observation of events. His knowledge must suffice to explain all unusual occurrences, and his art to combat them. He is the scholar, the specialist, the expert on the subject of chance occurrences, and at the same time the keeper of the archives of the tribe's traditional lore. Surrounded by respect and fear, he enjoys great authority, yet not so great but that his tribe is secretly convinced that their neighbours have a sorcerer who is stronger than theirs.” (Archaic Man, p. 135-136)

Like tribes advised by the rain-maker who knew to build villages on hills in order to benefit from more favorable weather patterns, or the psychoanalyst who recognized the benefits of confession, these ancient minds had not yet been differentiated, with the external and internal happenings of the world still divinely intertwined in one cosmic mystery.

In this light, William Frazer’s The Golden Bough offers some penetrating insights into the world of archaic magic and making, and why Jung perhaps had such a preference for the archaic world.

For instance, Frazer describes the “rain-maker”:

“Hence in savage communities the rain-maker is a very important personage; and often a special class of magicians exists for the purpose of regulating the heavenly water-supply. The methods by which they attempt to discharge the duties of their office are commonly, though not always, based on the principle of homoeopathic or imitative magic. If they wish to make rain they simulate it by sprinkling water or mimicking clouds: if their object is to stop rain and cause drought, they avoid water and resort to warmth and fire for the sake of drying up the too abundant moisture. Such attempts are by no means confined, as the cultivated reader might imagine, to the naked inhabitants of those sultry lands like Central Australia and some parts of Eastern and Southern Africa, where often for months together the pitiless sun beats down out of a blue and cloudless sky on the parched and gaping earth.”

Frazer describes the role of rainmakers among the Wagogo peoples of East Africa:

“…Among the Wagogo of East Africa the main power of the chiefs, we are told, is derived from their art of rain-making. If a chief cannot make rain himself, he must procure it from some one who can. Again, among the tribes of the Upper Nile the medicine men are generally the chiefs. Their authority rests above all upon their supposed power of making rain, for rain is the one thing which matters to the people in those districts, as if it does not come down at the right time it means untold hardships for the community. It is therefore small wonder that men more cunning than their fellows should arrogate to themselves the power of producing it, or that having gained such a reputation, they should trade on the credulity of their simpler neighbours.”

As Frazer observes, at the heart of these societies was an unwavering belief in the leader’s magical powers:

“But in savage society there is commonly to be found in addition what we may call public magic, that is, sorcery practised for the benefit of the whole community. Wherever ceremony of this sort are observed for the common good, it is obvious that the magician ceases to be merely a private practitioner and becomes to some extent a public functionary. The development of such a class of functionaries is of great importance for the political as well as the religious evolution of society. For when the welfare of the tribe is supposed to depend on the performance of these magical rites, the magician rises into a position of much influence and repute, and may readily acquire the rank and authority of a chief or king. The profession accordingly draws into its ranks some of the ablest and most ambitious men of the tribe, because it holds out to them a prospect of honor, wealth, and power such as hardly any other career could offer. The acuter minds perceive how easy it is to dupe their weaker brother and to play on his superstition for their own advantage. Not that the sorcerer is always a knave and impostor he is often sincerely convinced that he really possess those wonderful powers which the credulity of his fellows ascribes to him. But the more sagacious he is, the more likely he is to see through the fallacies which he imposes on duller wits. Thus the ablest members of the profession must tend to be more or less conscious deceivers; and it is just these men who in virtue of their superior ability will generally come to the top and win for themselves positions of the highest dignity and the most commanding authority.”

But perhaps Jung and Frazer were on to something. Maybe our modern world is still in some significant part shaped by “rain-makers” and magicians of various pedigrees? Perhaps they’ve simply been operating under different, more official-sounding titles.

From Trance to Transcendence: Reflections on Saving a Dying Republic

As previously explored, rhetoric, propaganda, and the “magical” qualities of language have been used to shape mass opinion for thousands of years. Plato in his time observed this phenomenon throughout the socio-politico-cultural matrix of Ancient Athens. Book X of

Jung argues that modern progress and material security have been useful in creating the illusion that man is a creature of reason capable of directing his own fate. The “magic of the jungle” served as a friendly reminder that as much as we might like to ascribe rational causes to all reality, un-intelligible powers and an arbitrary will are an inescapable reality as soon as man departs from his quaint city dwellings.

Whereas archaic man was more easily disposed to externalizing these psychical forces, thereby being keenly aware of the demon-haunted woods, cursed lagoons or ominous weather patterns, man had simply internalized and suppressed these psychical projections; he relied on the fortifications of modern science and progress to shield himself from a higher arbitrary will and the “capricious” forces dominating the universe at large. And he did so, we are told, by largely mechanical and artificial means.

Jung writes:

“It is a rational presupposition of ours that everything has a natural and perceptible cause. We are convinced of this. There is no legitimate place in our world for invisible, arbitrary, and so-called supernatural forces… We distinctly resent the idea of invisible and arbitrary forces, for it is not so long ago that we made our escape from that frightening world of dream and superstitions, and constructed for ourselves a picture of the cosmos worthy of rational consciousness—that latest and greatest achievement of man. We are now surrounded by a world that is obedient to rational laws.” (Archaic Man p. 130)

However, as Jung insists, the arbitrary will which archaic man regarded with awe and reverence was still capable of haunting modern man, even before the bulwark of modern rationality. In the modern world, Jung believed it took the form of unconscious projections and psychical outbursts, whose murky, nebulous sources still bubbled to the surface under the right circumstances. The psyche, Jung believed, knows better, and will not let him forget the magic and power of a higher divine will, beyond his understanding.

Jung argued that this indiscernible arbitrary power still enticed modern man, which manifested itself in the twentieth century’s obsession with psychoanalysis and psychic phenomena, including aliens:

“This ‘psychological’ interest of the present time shows that man expects something from psychic life which he has not received from the outer world: something which our religions, doubtless, ought to contain, but no longer do contain—at least for the modern man. The various forms of religion no longer appear to the modern man to come from within—to be expressions of his own psychic life; for him they are the with things of the outer world.” (The Modern Spiritual Problem, p. 206)

Jung specifically characterized this fascination as man’s innate hunger for mystical and religious experience, especially Gnostic currents concerned with the “experiential” dimensions of religion:

“The passionate interest in these movements arises undoubtedly from psychic energy which can no longer be invested in obsolete forms of religion. For this reason such movements have a truly religious character, even when they pretend to be scientific

“I do not believe that I am going too far when I say that modern man, in contrast to our nineteenth-century brother, turns his attention to the psyche with very great expectations ; and that he does so without reference to any traditional creed, but rather in the Gnostic sense of religious experience.”

For Jung, the field of modern psychoanalysis and a deeper investigation of the occult world of the “psyche” were the door by which ancient and arcane schools could be revived and brought back into the center of modern man’s spiritual life, setting him free at last.

But are Dr. Jung’s observations correct, or have some chapters in man’s history been overlooked, or perhaps consciously obscured?

An Archaic Revival?

In her book on the occult history of the Renaissance, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Frances Yates describes the fundamental shift in man’s self-image which began to emerge during the Renaissance:

“The Greeks with their first class mathematical and scientific brains made many discoveries in mechanics and other applied sciences but they never took whole-heartedly, with all their powers, the momentous step which western man took at the beginning of the modern period of crossing the bridge between the theoretical and the practical, of going all out to apply knowledge to produce operations. Why was this? It was basically a matter of the will. Fundamentally, the Greeks did not want to operate. They regarded operations as base and mechanical, a degeneration from the only occupation worthy of the dignity of man, pure rational and philosophical speculation. The Middle Ages carried on this attitude in the form that theology is the crown of philosophy and the true end of man is contemplation; any wish to operate can only be inspired by the devil.” (p. 156)

For over a millennium the cosmic order as it had been understood was unchanging, static, and man was relegated to the lowermost point. This was the reigning view during the Middle Ages, until the Earth’s position within the universe was called into question for the first time in a very long time. New breakthroughs in scientific method and epistemology made the rebirth of Classical Greek learning and science possible, now informed by a Judeo-Christian image of man.

During the Middle Ages, it was believed that the celestial bodies circled in the heavens in perfect uniform motions, simply because it was thought the most perfect order, and God had fashioned the most perfect (i.e. unchanging) creation. The heavens were encased by crystalline spheres; and all spheres were determined by an absolutely perfect and divine hierarchy. As far as participation within this divine order was concerned, the best man could hope for was to use formulaic logic and syllogistic reasoning to learn how to manipulate phenomena within the earthly sphere, without ever knowing why the universe functioned the way it did and not otherwise. But since creation was understood to be already completed and nothing could be done to change or improve it, metaphysical speculation and contemplation of God’s perfected work was considered the highest ideal.

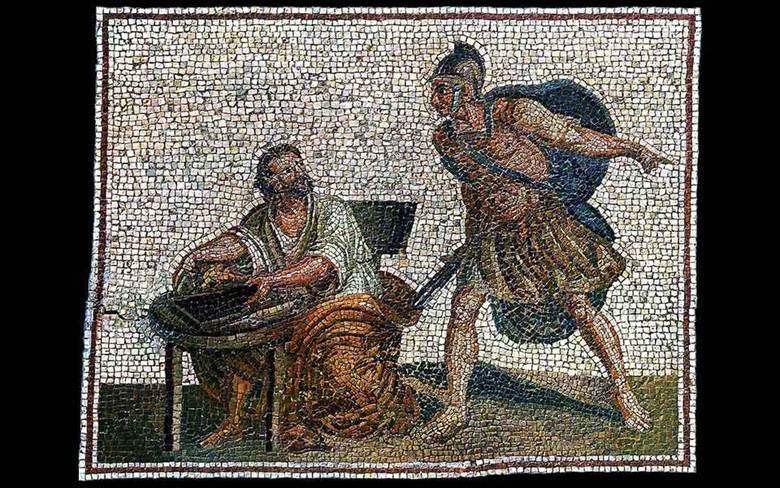

Reflections on Ideal Science and Art: Schiller’s “Archimedes and the Student”

We’ll be publishing regular new translations and analysis for our subscribers, all of which will be appearing in my new book of Schiller translations. We begin this new year with reflections on the ideal of science and art, as explored in Schiller’s “Archimedes and the Student.”

This system first began to break down when the Earth’s position within the cosmic hierarchy was called into questioned by the philosopher, theologian and diplomat Nicholas of Cusa. With a series of philosophical arguments that would revolutionize methods of science and statecraft, Cusa demonstrated that the Earth could not be at the center of the universe—for there was no fixed center. By effectively moving Earth’s position, man’s place within the universe was also called into question for the first time in centuries. As we’ll see, this epistemological revolution began with the publication of Cusa’s De Docta Ignorantia (On Learned Ignorance) in 1440, setting into the motion the development of modern astronomy—mankind’s oldest science—ultimately leading to the publication of Kepler’s New Astronomy (1609) and Harmony of the World (1619) i.e. modern astrophysics.

Keying off Cusa’s observations regarding the imperfection of human sensory observation, Kepler wrote:

“The testimony of the ages confirms that the motions of the planets are orbicular. It is an immediate presumption of reason, reflected in experience, that their gyrations are perfect circles. For among figures, it is circles, and among bodies, the heavens, that are considered the most perfect. However, when experience is seen to teach something different to those who pay careful attention, namely, that the planets deviate from simple circular paths, it gives rise to a powerful sense of wonder, which at length drives men to look into causes.”

The main obstacle to any revolution in astronomy, and therefore re-evaluation of man’s place within the cosmos, was the artificially imposed Aristotelian dogma which traced an eternally dividing line between the Earth and the Heavens. Imprecise observations of the celestial order were overlooked in favor of upholding an ancient dogma concerning man’s place within the universe.

For Aristotle, the heavenly and earthly worlds were incompatible, with the infinite mind of God—the Maximum—being incommensurate with his finite creation—the minimum—man. By the standards of crude Aristotelian logic, something could not be both finite and infinite, man and God, the Maximum and the Minimum. The mind of man could not fathom the mind of the Creator, and thus understand the nature of creation and its intent, let alone consciously act on the process.

Despite this dogma, which was the logical conclusion of Aristotle’s Law of Excluded Middle and Law of Non-Contradiction, a few Socratic minds were able to use their intellects to overthrow the tenuous logic and formalism that had restricted philosophical inquiry for centuries.

In respect to the relationship between man and God, Cusa made the following remarks:

“For man is god, but not unqualifiedly, since he is man; therefore, he is a human god. Man is also world but is not contractedly all things, since he is man; therefore, man is a microcosm, or a human world. Therefore, the region of humanity encompasses, by means of its human power God and the entire world.” (Nicholas of Cusa—On Conjectures, II, xiv)

Cusa made a qualitative distinction between the Absolute Infinite or Maximum, and the unbounded nature of the contracted i.e. created world. While both the universe and mind were not infinite and absolute in an unqualified i.e. unconctracted manner, they were none the less boundless, such that their finite nature did not preclude an infinite capacity (or potential) for future development.

Cusa’s penetrating intellect was able to redefine the restrictive logic of Aristotelian discursive reasoning by recognizing the higher faculty of intellect, where opposites like above and below, maximum and minimum, finite and infinite are necessarily resolved, given that all oppositions are resolved in God. Cusa called his revolutionary new approach the method of “Learned Ignorance.”

This change was symbolically foreshadowed by Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, where man finally ascends to Heaven and learns how to uncover the workings of the divine order using the power of his intellect, which Dante depicts Socratically through his dialogue with Beatrice, the Saints, Philosophers and other learned persons across history.

In terms of art, this god-like potential or “capax dei” was expressed in the subtle and living expressions of the human form by Renaissance artists. The sublimity of the earlier Classical Greeks was now informed by a new moral clarity and intellectual vision.

For the Renaissance mind, the tender youth David could vanquish the tyrannical power of a brute Philistine using his intellect; the virtue of a Judith could overcome the blind power lust of an evil Holofernes; and a Perseus could use his creative insight to wield the goddess Athena’s shield and slay the petrifying Gorgon. These promethean symbols invited a new kind of inquiry into the workings of the divine order, nature and mind.

For the first time in ages, man began to question his basic knowledge and assumptions about the universe. Faith based on Reason supplanted a purely blind faith, the former being propelled by the conviction that God had fashioned the universe according to Reason—rather than some arbitrary and unfathomable will—such that man who was made in his image could willfully choose to cultivate his higher faculties, and thereby learn to unfold the enfolded universe in an intelligible way.

Echoing Plato, Cusa wrote that man the microcosm is “the living description of eternal and infinite wisdom… Through the activity of our intellective life we are able to find within ourselves the object of our search.” (Nicholas of Cusa, The Laymen on Wisdom and Mind, III; On Mind).

The result was a newfound faith in man’s own ability to participate in eternal creation by cultivating the same divine qualities within his own sphere of action. In this sense, Cusa understood the Maximum to be inherent in the Minimum.

Recourse to soothsayers and astrologists, drawing down the celestial influences with sympathetic magic or blind faith in miracles was no longer considered the best means of fathoming the mystery man (or God); rather, the miracle was that man could willfully explore this mystery himself. To the degree man chose to cultivate his discerning faculties and become more learned in his ignorance, he could fathom the fathomless, from which all things originated and to which all things returned.

So, Nicholas of Cusa wrote:

“Lord, Thou hast given me my being of such a nature that it can continually make itself more able to receive thy grace and goodness. And this power, which I have of Thee, wherein I have a living image of Thine almighty power, is free will.”

However, occultists and “traditionalist” thinkers have long looked back on this miraculous shift in man’s self-image and argued that the suppression of the deeper archaic, traditional and “non-rational” aspects of man dominant in pre-Renaissance times meant civilization had lost access to the more intuitive and “spiritual” dimensions of reality. Deprived of this ineffable source of mystery, man would ultimately be left empty, doe-eyed, severed from all previous tradition, and blinded by the very Promethean fire he resolutely wrested from the Olympian hierarchy.

But is this the reason for man’s haunting, or has he been consciously deceived by a clever cadre of modern magicians who would love nothing more than to see man relinquish his will to the mystery schools of old?

The key to answering this question is hinted at by some of Jung’s own reflections on his spiritual journey:

As far as I could see, the tradition that might have connected Gnosis with the present seemed to have been severed, and for a long time it proved impossible to find any bridge that led from Gnosticism—or neo-Platonism—to the contemporary world. But when I began to understand alchemy I realized that it represented the historical link with Gnosticism, and that a continuity therefore existed between past and present. Grounded in the natural philosophy of the Middle Ages, alchemy formed the bridge on the one hand to the past, to Gnosticism, and on the other into the future, to the modern psychology of the unconscious. (Memories, Dreams and Reflections, p. 201)

To unravel this mystery, in our next instalment we’ll delve into the occult or “hidden” history of the Renaissance, and the perversion of its most revolutionary concepts by leading occultists, Neoplatonists and alchemists across the ages.

Stay tuned for the next instalment, “The Power of Myth, Or The Alchemy of Modern Psychoanalysis”.

Escaping Huxley’s Island: Psychedelics, Scientific Paganism and the Changing Images of Man

Originally published on UK Column

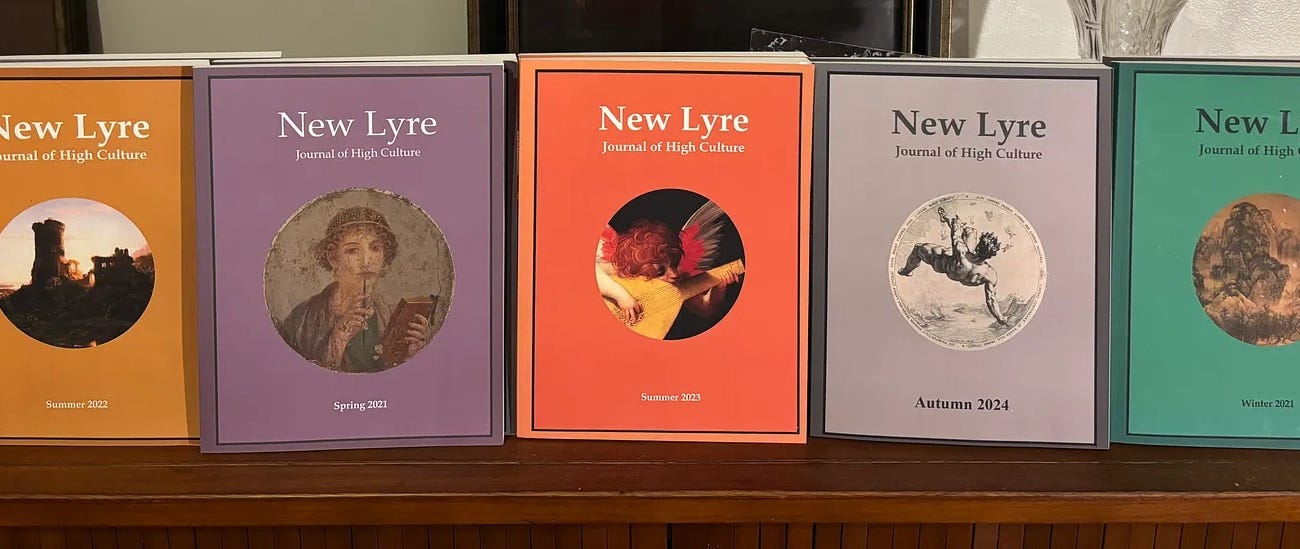

Read Our Magazine

Paid subscribers can access all issues of our New Lyre Magazine at the bottom of this page.

Curious which "agencies, agendas and political operations" have been used to "actively unmake modern Western civilization and the fruits of its progress" —and what “other” Renaissance they root to. If not psychological or philosophical in nature, then what? Revenge of mystical nerds? Mystery schools undone not by Christianity but their own shadow “schools of resentment?” which continue to seethe to this day with jazzy pop-adulterations of truth? My hunch here is that you’re trying to exorcize an ancient irrational ghoul for the Neoplatonist ideal, and while true rationality is fast losing its lustre and hold on Western Civ, Jung was right to suspect it as way too one-sided for its own good. The bigger the front, the bigger the back … And the digital cultural castrophe is sorely Promethean. Still, I look forward to reading on. Thanks for doing such elaborate and dedicated digging.

The springs of being somehow got built into Nature it would appear. Nature being the only thing life can be traced to. Some thinkers have seen its apparently indefatigable operation as unbenign. It's easy to see why. It can certainly seem like a killing machine that can't be stopped. A machine that mows while it sows.

Imagination breeds possibilities, and possibilities can haunt and frighten. No one can see past their surrounds, so backgrounds are made up. Even ones that are contradicted by all one can know.

All I know is that in this game, the one that has been played over and over ad infinitum on planet earth, the dealer has always held all the cards. Maybe a fluke of evolution will eventually turn the tables. But personally, I think their turning will depend on a different sort of lucky accident. Like William Tell's arrow miraculously hitting some tiny speck it was aimed at, or a wave of antimatter leaving a swath of space void.

Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow comes to mind. We shall see what the morrow brings. Likely a repeat of today. But possibility is limitless.

I wish your new book a good reception. Was asking myself what category of lit. it might fit into. Historical analysis? Have you found a publisher I wonder? Or are you maybe intending to publish

it yourself?