Originally published by Antigone Journal

δέδοικα μή τι πὰρ θεοῖς

ὰμβλακὼν τιμὰν πρὸς ὰνθρώπων ὰμείψω.

It must be for some sin

that the gods grant me honor among men.

—Ibycus of Rhegium

In Friedrich Schiller’s poem “The Cranes of Ibycus”, presented in a new English translation below, the poet Ibycus is murdered in a forest by a troop of thugs and thinks himself alone. There appears to be no avenging justice or potential witness to right the historical wrongs or reveal what truly happened that day. By the time the poet’s disfigured body is discovered in a forest, his murderers have long since fled.

While today’s Western world is haunted by similar historical injustices, we may still look to the greatest works of Classical art and poetry as a source of wisdom and insight for all times. After all, the nature of any truly timeless classic is that it serves as an inexhaustible fount of wisdom for mankind, and has the power to replenish and uplift the soul of people in any age.

One unique example is Friedrich Schiller’s “Cranes of Ibycus”. The poem was composed during the height of what’s known today as Germany’s Weimar Classical period (roughly 1772–1805), during which the poets Goethe and Schiller flourished, reviving interest in the Classical Greek tradition at the height of Germany’s cultural maturation. Schiller’s poem revisits the legend surrounding the life of the Ancient Greek poet Ibycus. Schiller used the myth as poetic material to revisit thematically the Ancient Greek notion of divine justice, as embodied by Nemesis and the chthonic goddesses of retribution, the Erinyes (or Furies).

The personification of justice and retribution, Nemesis represented the inescapable agent of a person’s demise, which craven killers and foolhardy fiends courted at their own risk. Like Shakespeare’s plays or Classical Greek tragedy, Schiller’s ballad reminds us that a higher system of law exists, one that remains indomitable even in the face of the world’s fiercest tyrants and most ruthless murderers. When this higher system of law is violated, Nemesis makes her dark entrance onto the stage.

Ibycus in History

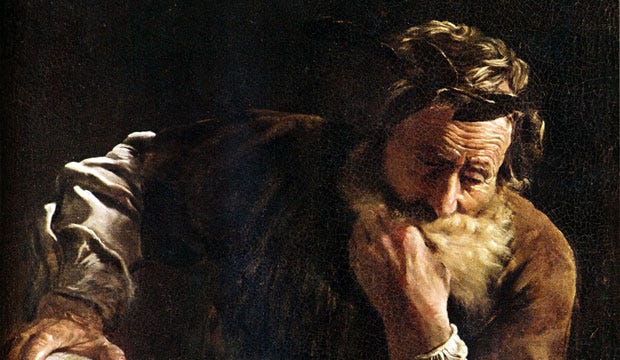

Schiller’s ballad recounts the story of the Greek poet Ibycus, but what do we really know about the man? Our knowledge of Ibycus (fl. mid/2nd half of the 6th cent. BC) comes both by way of myth and historical accounts. He was a renowned lyric poet from Rhegium (modern Reggio di Calabria), one of many Greek colonies in southern Italy (Magna Graecia, “Greater Greece”). Something of a male equivalent to Sappho (c. 610–570 BC), he was famous for his passionate love lyrics, which dealt with the poet’s own trepidation regarding love and the overwhelming power of erotic rapture.

While most of his poetry only survives in fragments, the little which remains allows us to appreciate why he would have been among the favorites of the librarians of Alexandria and ranked among the nine canonical lyric poets of Ancient Greece.

Take the following example by the ancient lyricist of love:

Ἔρος αὖτέ µε κυανέοισιν ὑπὸ

βλεφάροις τακέρ’ ὄµµασι δερκόµενος

κηλήµασι παντοδαποῖς ἐς ἄπει-

ρα δίκτυα Κύπριδος ἐσβάλλει·

ἦ µὰν τροµέω νιν ἐπερχόµενον,

ὥστε φερέζυγος ἵππος ἀεθλοφόρος ποτὶ γήρᾳ

ἀέκων σὺν ὄχεσφι θοοῖς ἐς ἅµιλλαν ἔβα.Eros again, gazing beneath purple eyelids

with piercing eyes, draws me with enveloping

webbery into the multitudinous

enchanting embracements of the Cyprian;

and his mere coming makes my body tremble,

as the horse shudders when the charioteer

rushes headlong into the swift clash of chariots. (trans. Carey Jobe)

The poet uses the harrowing image of an experienced racehorse who is all-too-well acquainted with the impassioned ordeal that is to come. He reacts with helpless dread as the charioteer forces him again into the race. Flung into the clash of chariots by the unbridled power of the charioteer, in this case represented by Eros, the image serves as an astonishing metaphor for the potentially overwhelming experience of erotic rapture, and its effects on even the most seasoned and fearless steeds. The lines describe a well-versed lover who feels overmastered. The colliding images of erotic sensuality and physical violence in these seven lines were, to the ancients, a distinguishing feature of Ibycus’ poetry.

The literary career of Ibycus spanned two distinct Greek poetic schools. He sprang from the same poetic tradition that flourished among the Ancient Greek-speaking peoples of Southern Italy, as exemplified by the likes of another canonical Greek lyric poet, Stesichorus (c.630–555 BC). Also a native of Magna Graecia, Stesichorus developed a regional tradition of lyrical choral poetry performed in public competitions. These odes usually celebrated epic legends, such as the Fall of Troy, and the exploits of mythical heroes. Like his predecessor, Ibycus appears to have composed his earliest poetry in this tradition, as he was specifically categorized by the librarians of Alexandria as a choral-lyric poet. These longer mythological poems, of which brief fragments survive, would have recounted the epic cycles of Homer in a unique choral-lyric fashion influenced by the likes of Stesichorus.

Later, Ibycus moved to the island of Samos, where he became active at the court of the tyrant Polycrates. [1] Ibycus treated the legendary cycles of the Homeric tradition, as well as intimate personal lyrics, in his own memorable fashion; the poet himself would later become the stuff of egend. Schiller drew inspiration from sources such as Plutarch, Antipater of Sidon and the Suda, all of whom described the death of the poet and the intervention of cranes—the only witnesses to the poet’s untimely demise.

While travelling to the Isthmian games, Ibycus was ambushed by thieves and murdered in cold blood. However, a flock of cranes happened to be traveling over the scene of his murder. Later, the murderers were drawn to the same Isthmian games where the bard was expected to perform. Finally, the swarm appeared over the event just as the news of Ibycus’ murder becomes public. In sheer surprise, one of the murderers inadvertently incriminated himself by blurting out Ibycus’ name. Faced with a “what did they know and when did they know it?” moment, the murderers were forced to confess and were duly brought to justice.

Schiller’s Cranes

Schiller composed his retelling of the Ibycus legend during his friendly ballad competition with fellow poet Goethe in 1797, known as the “Year of the Ballad”. Among the famous ballads composed during that period were Schiller’s “Cranes of Ibycus” and his historical poem “The Ring of Polycrates”, along with Goethe’s “The Bride of Corinth” and “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”.

Schiller uses the Ibycus myth as an opportunity to immerse readers in the classical theatre culture of the age, while at the same time acquainting them with some of its loftiest themes of justice and natural law. In doing so, Schiller brings readers face to face with the principle of divine justice, embodied by the Erinyes, the chthonic goddesses of revenge, and Nemesis, the personification of divine justice.

In his Description of Greece, the traveling historian Pausanias (AD c.110–80) described the famous statue of the goddess Nemesis as follows:

About eight miles north of Marathon… is a sanctuary of Nemesis, the most implacable deity to men of violence. It is thought that the wrath of the goddess fell also upon the foreigners [i.e. the Persians] who landed at Marathon. For thinking in their pride that nothing stood in the way of their taking Athens, they were bringing a piece of Parian marble to make a trophy, convinced that their task was already finished. Of this marble Phidias made a statue of Nemesis, and on the head of the goddess is a crown with deer and small images of victory. In her left hand she holds an apple branch [her characteristic symbol], in her right hand a cup… (1.33.2)

The Ancient Greeks did not view the goddess as a daily presence, but understood her as a very real force in the universe, targeting those whose crimes flouted Natural Law in the most violent manner – such as the cold-blooded murder of one of Greece’s most beloved poets.

Schiller’s ballad echoes Shakespeare’s Macbeth, in which the sheer horror of Macbeth’s heinous murder becomes the very thing that dooms him. We find similar situations in the works of Edgar Allan Poe (including “The Black Cat”, “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “William Wilson”), and in Mozart’s opera Don Giovanniwhere the villainous Don Juan’s transgressions are so malevolent, and his behavior so degenerate, that demons crawl out of their portal and drag him down to Hell themselves. In such tragedies and Nemesis stories, the audience is presented with crimes and injustice of historic proportion, reminding us that, while the correctives for such crimes are never instantaneous, the universe has its own creative ways of rendering justice.

Tyrants blinded by their pride and lust for power may believe any such higher principles are the mere fancy of superstitious people, but history reveals “there is a limit to the tyrant’s power”, as Schiller famously writes in Wilhelm Tell.

The Ballad: Formal Considerations

Formally speaking, The Cranes of Ibycus is an epic ballad composed in Italian-style ottava rima across 23 stanzas. Schiller manages to set up a complex series of transitions and narrative twists that take us from the initial happy opening of Ibycus’ journey to Corinth, his gruesome murder and the ensuing chaos at the Isthmian games, through

Combining narrative poetry with tragic themes and musical drama, Schiller’s ballad weaves various elements of Classical Greek drama and epic into the formal characteristics of German folk song to create a sublimely innovative and memorable ballad. Notably, Schiller added the appearance of the chorus of the Erinyes from Aeschylus’ Eumenides to his retelling of the Ibycus story. This novel addition serves as a dramatic device which allowed Schiller to elaborate the theme of divine justice in an unexpected and original manner.

The celebrated Classical philologist Wilhelm von Humboldt had the following to say about the ballad in a letter congratulating Schiller:

There is a greatness and a sublimity [in the Cranes], which is again completely their own. Especially from the moment the theater is mentioned, the depiction is godly. The painting of the amphitheater and the congregation is lively, great and clear, already the names of the peoples transpose one to such happier times, that I know of scarcely anything more magnificent for the fantasy. And then the chorus of the Eumenides, as it appears in its frightful greatness, wanders around the theater, and finally disappears, horrible even then. Here the language is at once so uniquely yours, and so appropriate for the task, that I cannot deny that I felt, in the chorus, something greater and something even higher than in the Greek of Aeschylus, as closely as you have followed him. Already this language, this verse-style, even the rhyme scheme make that which is otherwise unique to modern works unite with antiquity. The sublimity for fantasy and heart, which is so unique to Greek expression, achieves here, I believe, an increased greatness for the mind… The Ibycus has… an extraordinary substance; it moves deeply; it shakes one; it fascinates, and one must come back to it again and again. Surprisingly beautiful are the transitions, and you succeeded very well in the difficult narration of the development. [2]

In conclusion, with “The Cranes of Ibycus” the dramatic and historical literally coincide with the appearance of the Erinyes. It serves as a visceral embodiment of the poetic principle of justice and its universal role throughout human history. However stubbornly man may wish to avoid it, and however carelessly the craven and wretched choose to disregard it, none should forget that “Murder, though it have no tongue, will speak.”

Without further ado, then, we offer a fresh translation of Schiller’s celebrated ballad.

The Cranes of Ibycus

Friedrich Schiller

(trans. David Gosselin)

Towards the aulos howls and chariot games,

Where Greece assembled all its strains

Along the fabled shores of Corinth’s Isthmus,

The friend of gods, strode Ibycus.

Apollo granted him the muses’ charms,

Their music flowed from his young lips;

So went he on his way, with lyre in arms,

From Rhegium, with godly gifts.

Already Acrocorinth’s mountain ways

Beckoned the wanderer’s deep gaze.

But first, he must descend with hesitation

Into the spruces of Poseidon.

The air was still, then came a flapping sound:

He heard a flock of swarming cranes

Making their southward flight to warmer climes,

In feathery, grey echelons.

“Greetings, my fellow travelers who’ve kept

Me company across the sea!

Your presence seems like an auspicious sign,

Our fates and fortunes intertwine!

We’ve fared from distant principalities

And now pray for a dwelling place;

May kind souls show us hospitality,

And guard the stranger from disgrace!”

The god-elated bard drove anxiously

Ahead into the darkened grove,

When suddenly, nearby a narrow gorge,

Two thieves surprised him at a bridge.

The poet readied himself for a fight,

But soon, his weary hand sank low.

It strummed the lyre’s frail strings with sheer delight,

But never drew the tautened bow.

He implored men and gods alike for aid

But sadly, no assistance came;

However desperately he made his pleas,

No help arrived for his defence.

“So here, I guess, is where I’m meant to die,

Left at the hands of criminals,

To perish in a foreign land and lie

Abandoned like an animal.”

Then gravely wounded, prostrate on the ground,

He heard a sudden thrashing sound;

Just as he went to shut his dying eyes,

The flock of cranes swept through the skies.

“Without a mortal ear to hear my cries,

Cranes, you will be my witnesses,

And carry back the news of my demise.”

He spoke then shut his eye lids.

Not before long, the naked corpse was found

Strewn and disfigured on the ground;

His host in Corinth quickly recognized

The boy he hoped would win the prize.

“And this is how we reunite again,

When I had hoped to see you crowned,

To wreathe your temples with the sprigs of pine

And celebrate your bright renown.”

Everyone at Poseidon’s festival

Received the news of Ibycus’ fall;

His death shook every tribesman to his core,

And left a void in every heart.

Attendees rushed in impetuous throngs

Towards the acting Prytane,[3]

Demanding blood from those who did the wrong,

And urging justice for the slain.

But could a clue be found among the crowds

Thronging about in frantic hoards?

And might the celebrated festival

Lure out the wily criminal?

Were craven robbers those responsible,

Or killers spurred by jealousy?

Only Helios’ all-revealing rays

Unveils the truth with certainty.

But even now, perhaps, the killer walks

About the gathering and balks

At justice, proud of his unpunished crimes—

Though vengeance readies its designs.

Maybe he braves the presence of the gods

And walks before their blessed fanes,

Cloaking himself amid the busy crowds

Who came for theatre and the games.

Attending the event from far and near,

Members of every tribe appeared.

The teaming amphitheatre benches quaked

As floods of people warred for seats.

Writhing and rising like the anxious seas

Which surge beneath the tempest’s rage,

They climbed and crested up towards the sky,

In weltering, dramatic waves.

So many peoples and so many names

Had gathered for Isthmian games:

From Theseus’ town and Aulis’ strand,

From Phocis and the Spartan’s land,

And even from Asia’s distant shores,

Attendants hailed from everywhere.

Then from the stage they heard the choruses

Erupting into haunting wails.

Marching, according to their ancient habits,

In solemn, strict and measured steps,

Emerging from the darkness of the stage,

They circled round the theatre’s edge.

No earthly woman ever walked like them,

They weren’t of this world of mortals;

Their bodies dwarfed the stoutest Grecian men—

Were unlike any from earth’s portals.

Their loins were covered up with mantle black,

While in their fleshless hands there swung

A torch, which tinted all with twilight redness.

Their cheeks were hollow, starved and bloodless.

Around their brows, on which the curly locks

Of mortals usually land,

Adders and vipers violently writhed and shot

Dark poisons from their swollen glands.

Now standing upright in a spectral ring,

They started singing their dire hymn;

Chant after chant, it snaked into all hearts,

Bounding men’s sinful souls and thoughts.

Digging and gnawing at their tortured domes,

The song of the Erinyes’ roared

Into the air; it weaved around each’s bones,

In strains for which lyres have no chord.

“Blessed is he who free from guilt and sin

Honors his childlike soul and kin!

He may avoid our steely vengeance shafts—

And keep upon life’s faithful paths.

Yet woe upon him who performs the deed

Of murder hidden out of sight.

We’ll trace his steps wherever he may be—

We, the dark daughters of the night.

“If he believes he might escape his fate,

We’ll spread our wings and quickly lay

Our painful snares around his fleeting feet,

Until the ground and his face meet.

We’ll haunt the guilty ‘til his final breath,

Careless of whether he repents;

We’ll chase him even to the netherworld

Of shades—and still never relent.”

They chant in rhythmic circles, weaving round;

The stillness of the dead surrounds

The hallowed theatre’s open air,

As if the deity drew near.

Solemnly, in their custom’s sacred way,

They moved along the stage’s round,

And then, in careful, strict and measured steps,

They vanished in the dark background.

Still wavering between truth and deceit,

Doubt swung around their troubled hearts;

The crowds paid homage to the mighty force

Which makes way for the Fates’ stern course.

Unseen, beyond our fathomed earthly skies,

They thread each mortal’s destined plight,

Announcing themselves in the depths of hearts,

Yet never entering the light.

Then from the crowds they heard in sheer surprise

An unexpected voice ring out;

“Look up! Look up, behold Timotheus,

Those are the cranes of Ibycus!”

The gaping heavens quickly turned to night,

Just as above the theatre, crowds

Beheld a swarm of cranes in dusky flight,

Emerging from a darker cloud.

“Of Ibycus”—that cherished, blessed name.

Sorrow arises within each breast,

Like rushing waves upon the harrowed sea,

From mouth to mouth it flew swiftly.

“Of Ibycus, whom we presently mourn?

Who was so recently just slain?

What could that stranger’s words possibly mean?

What did he say about those cranes?”

The questions and entreaties quickly grew,

And soon with lightning speed each knew

The power flooding through their hearts: “Behold

The might of the Eumenides!

The shade of Ibycus has been appeased,

The guilty murderers confessed!

Arrest the one who uttered those last words,

And him to whom they were addressed!”

The words had barely left the killer’s mouth,

Which no true fiend dares think aloud;

In vain! His sagging jaw and trembling lips

Brought dark realities to light.

They’re swiftly dragged before the judge’s stall—

A tribunal, for all the witnesses.

The criminals indict themselves and fall

Beneath the beams of Nemesis.

Translation © 2025 David B. Gosselin

Die Kraniche des Ibykus

Friedrich Schiller

Zum Kampf der Wagen und Gesänge,

Der auf Korinthus’ Landesenge

Der Griechen Stämme froh vereint,

Zog Ibykus, der Götterfreund.

Ihm schenkte des Gesanges Gabe,

Der Lieder süßen Mund Apoll,

So wandert’ er, an leichtem Stabe,

Aus Rhegium, des Gottes voll.

Schon winkt auf hohem Bergesrücken

Akrokorinth des Wandrers Blicken,

Und in Poseidons Fichtenhain

Tritt er mit frommem Schauder ein.

Nichts regt sich um ihn her, nur Schwärme

Von Kranichen begleiten ihn,

Die fernhin nach des Südens Wärme

In graulichtem Geschwader ziehn.

“Seid mir gegrüßt, befreundte Scharen!

Die mir zur See Begleiter waren,

Zum guten Zeichen nehm ich euch,

Mein Los, es ist dem euren gleich.

Von fernher kommen wir gezogen

Und flehen um ein wirtlich Dach.

Sei uns der Gastliche gewogen,

Der von dem Fremdling wehrt die Schmach!”

Und munter fördert er die Schritte

Und sieht sich in des Waldes Mitte,

Da sperren, auf gedrangem Steg,

Zwei Mörder plötzlich seinen Weg.

Zum Kampfe muß er sich bereiten,

Doch bald ermattet sinkt die Hand,

Sie hat der Leier zarte Saiten,

Doch nie des Bogens Kraft gespannt.

Er ruft die Menschen an, die Götter,

Sein Flehen dringt zu keinem Retter,

Wie weit er auch die Stimme schickt,

Nicht Lebendes wird hier erblickt.

“So muß ich hier verlassen sterben,

Auf fremdem Boden, unbeweint,

Durch böser Buben Hand verderben,

Wo auch kein Rächer mir erscheint!”

Und schwer getroffen sinkt er nieder,

Da rauscht der Kraniche Gefieder,

Er hört, schon kann er nichts mehr sehn,

Die nahen Stimmen furchtbar krähn.

“Von euch, ihr Kraniche dort oben,

Wenn keine andre Stimme spricht,

Sei meines Mordes Klag erhoben!”

Er ruft es, und sein Auge bricht.

Der nackte Leichnam wird gefunden,

Und bald, obgleich entstellt von Wunden,

Erkennt der Gastfreund in Korinth

Die Züge, die ihm teuer sind.

“Und muß ich dich so wiederfinden,

Und hoffte mit der Fichte Kranz

Des Sängers Schläfe zu umwinden,

Bestrahlt von seines Ruhmes Glanz!”

Und jammernd hören’s alle Gäste,

Versammelt bei Poseidons Feste,

Ganz Griechenland ergreift der Schmerz,

Verloren hat ihn jedes Herz.

Und stürmend drängt sich zum Prytanen

Das Volk, es fordert seine Wut,

Zu rächen des Erschlagnen Manen,

Zu sühnen mit des Mörders Blut.

Doch wo die Spur, die aus der Menge,

Der Völker flutendem Gedränge,

Gelocket von der Spiele Pracht,

Den schwarzen Täter kenntlich macht?

Sind’s Räuber, die ihn feig erschlagen?

Tat’s neidisch ein verborgner Feind?

Nur Helios vermag’s zu sagen,

Der alles Irdische bescheint.

Er geht vielleicht mit frechem Schritte

Jetzt eben durch der Griechen Mitte,

Und während ihn die Rache sucht,

Genießt er seines Frevels Frucht.

Auf ihres eignen Tempels Schwelle

Trotzt er vielleicht den Göttern, mengt

Sich dreist in jene Menschenwelle,

Die dort sich zum Theater drängt.

Denn Bank an Bank gedränget sitzen,

Es brechen fast der Bühne Stützen,

Herbeigeströmt von fern und nah,

Der Griechen Völker wartend da,

Dumpfbrausend wie des Meeres Wogen;

Von Menschen wimmelnd, wächst der Bau

In weiter stets geschweiftem Bogen

Hinauf bis in des Himmels Blau.

Wer zählt die Völker, nennt die Namen,

Die gastlich hier zusammenkamen?

Von Theseus’ Stadt, von Aulis’ Strand,

Von Phokis, vom Spartanerland,

Von Asiens entlegener Küste,

Von allen Inseln kamen sie

Und horchen von dem Schaugerüste

Des Chores grauser Melodie,

Der streng und ernst, nach alter Sitte,

Mit langsam abgemeßnem Schritte,

Hervortritt aus dem Hintergrund,

Umwandelnd des Theaters Rund.

So schreiten keine irdschen Weiber,

Die zeugete kein sterblich Haus!

Es steigt das Riesenmaß der Leiber

Hoch über menschliches hinaus.

Ein schwarzer Mantel schlägt die Lenden,

Sie schwingen in entfleischten Händen

Der Fackel düsterrote Glut,

In ihren Wangen fließt kein Blut.

Und wo die Haare lieblich flattern,

Um Menschenstirnen freundlich wehn,

Da sieht man Schlangen hier und Nattern

Die giftgeschwollenen Bäuche blähn.

Und schauerlich gedreht im Kreise

Beginnen sie des Hymnus Weise,

Der durch das Herz zerreißend dringt,

Die Bande um den Sünder schlingt.

Besinnungsraubend, herzbetörend

Schallt der Errinyen Gesang,

Er schallt, des Hörers Mark verzehrend,

Und duldet nicht der Leier Klang:

“Wohl dem, der frei von Schuld und Fehle

Bewahrt die kindlich reine Seele!

Ihm dürfen wir nicht rächend nahn,

Er wandelt frei des Lebens Bahn.

Doch wehe, wehe, wer verstohlen

Des Mordes schwere Tat vollbracht,

Wir heften uns an seine Sohlen,

Das furchtbare Geschlecht der Nacht!

“Und glaubt er fliehend zu entspringen,

Geflügelt sind wir da, die Schlingen

Ihm werfend um den flüchtgen Fuß,

Daß er zu Boden fallen muß.

So jagen wir ihn, ohn’ Ermatten,

Versöhnen kann uns keine Reu,

Ihn fort und fort bis zu den Schatten

Und geben ihn auch dort nicht frei.”

So singend, tanzen sie den Reigen,

Und Stille wie des Todes Schweigen

Liegt überm ganzen Hause schwer,

Als ob die Gottheit nahe wär.

Und feierlich, nach alter Sitte

Umwandelnd des Theaters Rund

Mit langsam abgemeßnem Schritte,

Verschwinden sie im Hintergrund.

Und zwischen Trug und Wahrheit schwebet

Noch zweifelnd jede Brust und bebet

Und huldigt der furchtbarn Macht,

Die richtend im Verborgnen wacht,

Die unerforschlich, unergründet

Des Schicksals dunklen Knäuel flicht,

Dem tiefen Herzen sich verkündet,

Doch fliehet vor dem Sonnenlicht.

Da hört man auf den höchsten Stufen

Auf einmal eine Stimme rufen:

“Sieh da! Sieh da, Timotheus,

Die Kraniche des Ibykus!” –

Und finster plötzlich wird der Himmel,

Und über dem Theater hin

Sieht man in schwärzlichtem Gewimmel

Ein Kranichheer vorüberziehn.

“Des Ibykus!” – Der teure Name

Rührt jede Brust mit neuem Grame,

Und, wie im Meere Well auf Well,

So läuft’s von Mund zu Munde schnell:

“Des Ibykus, den wir beweinen,

Den eine Mörderhand erschlug!

Was ist’s mit dem? Was kann er meinen?

Was ist’s mit diesem Kranichzug?” –

Und lauter immer wird die Frage,

Und ahnend fliegt’s mit Blitzesschlage

Durch alle Herzen. “Gebet acht!

Das ist der Eumeniden Macht!

Der fromme Dichter wird gerochen,

Der Mörder bietet selbst sich dar!

Ergreift ihn, der das Wort gesprochen,

Und ihn, an den’s gerichtet war.”

Doch dem war kaum das Wort entfahren,

Möcht er’s im Busen gern bewahren;

Umsonst, der schreckenbleiche Mund

Macht schnell die Schuldbewußten kund.

Man reißt und schleppt sie vor den Richter,

Die Szene wird zum Tribunal,

Und es gestehn die Bösewichter,

Getroffen von der Rache Strahl.

David Gosselin is a poet, translator, and researcher in Montreal, Canada. He is Editor-in-Chief of The Chained Muse and publishes New Lyre Magazine. He is currently working on a book of Schiller translations, due out summer 2025. His poems, recordings and historical deep dives can be found on Substack at Age of Muses. He now hosts a poetry fireside chat series where writers join him for roundtable discussions and performances of classical works and original compositions. He has previously written for Antigone on Schiller, Cassandra and the rebirth of tragedy.

A special thanks to Carey Jobe for his excellent translations of the original Ancient Greek from Ibycus. And a special thanks to Dana Gioia for his input on the English translation of Schiller’s poem.

Notes

⇧1See Schiller’s treatment of the story of the tyrant Polycrates and his fate in “The Ring of Polycrates”.

⇧2Letter of December 7, 1797, translation taken from Rosa Tennenbaum, “1797, The ‘Year of the Ballad’—In the Poets’ Workshop,” Fidelio 7.2 (Spring, 1998) 61–77, at 76.

⇧3As Schiller writes in his “Legislation of Lycurgus and Solon”: “In the middle of Athens was a large public square, surrounded by statues of gods and heroes, called the prytaneum. The senate assembled in this place, so senators were called prytanes. A prytane was required to have a flawless character and stainless reputation. No spendthrift, no one who disrespected his father, no one who had ever been drunk even once, should consider applying for this office.”

Discover more of Schiller’s work

The Proverbs of Confucius by Friedrich Schiller

The stripling sets sail on the ocean with a thousand masts.

Reflections on Ideal Science and Art: Schiller’s “Archimedes and the Student”

We’ll be publishing regular new translations and analysis for our subscribers, all of which will be appearing in my new book of Schiller translations. We begin this new year with reflections on the ideal of science and art, as explored in Schiller’s “Archimedes and the Student.”

On Time and Eternity: Schiller's "Resignation"

“Time races onwards ceaselessly.”—It seeks the unchanging.

The Legislation of Lycurgus and Solon by Friedrich Schiller

To truly appreciate the nature of the Lycurgian plan, we must understand Sparta’s political situation at the time, and the conditions under which Lycurgus found Lacedaemon when he unveiled his new plan. Two kings held the same authority and simultaneously served as the heads of state; each was jealous of the other, and each was concerned with building his own following, to thus limit the authority of his rival. Their jealously had been inherited from the two previous kings, Prokles and Eurysthes, and their lineages down to Lycurgus, such that Sparta was constantly plagued by factional struggles. Each king sought to bestow more freedoms on the people to win their favor, and these gifts inspired insolence within the population, leading to insurrection. The…

Your scansion is getting a lot better.

I always prefer to indent the shorter lines, so as to bring out the structure of the poem. This is because art is about the transmutation of content into form. And it is this which gives art its healing effect, both for the artist and the audience. That form of course should emerge naturally from the content, and so help reconcile one to it.

This also means that irregular lines are easily seen for what they are.

Keep up the great work Brother